Namibia is a land of contrasts, the landscape rugged, and the distances far. Despite this harsh terrain the flora and flora has thrived here, adapting to the ruthless and somewhat unpredictable conditions. The abundance and variety of wildlife is astounding, from big game such as lion and elephant, to antelope, birds, reptiles and much more.

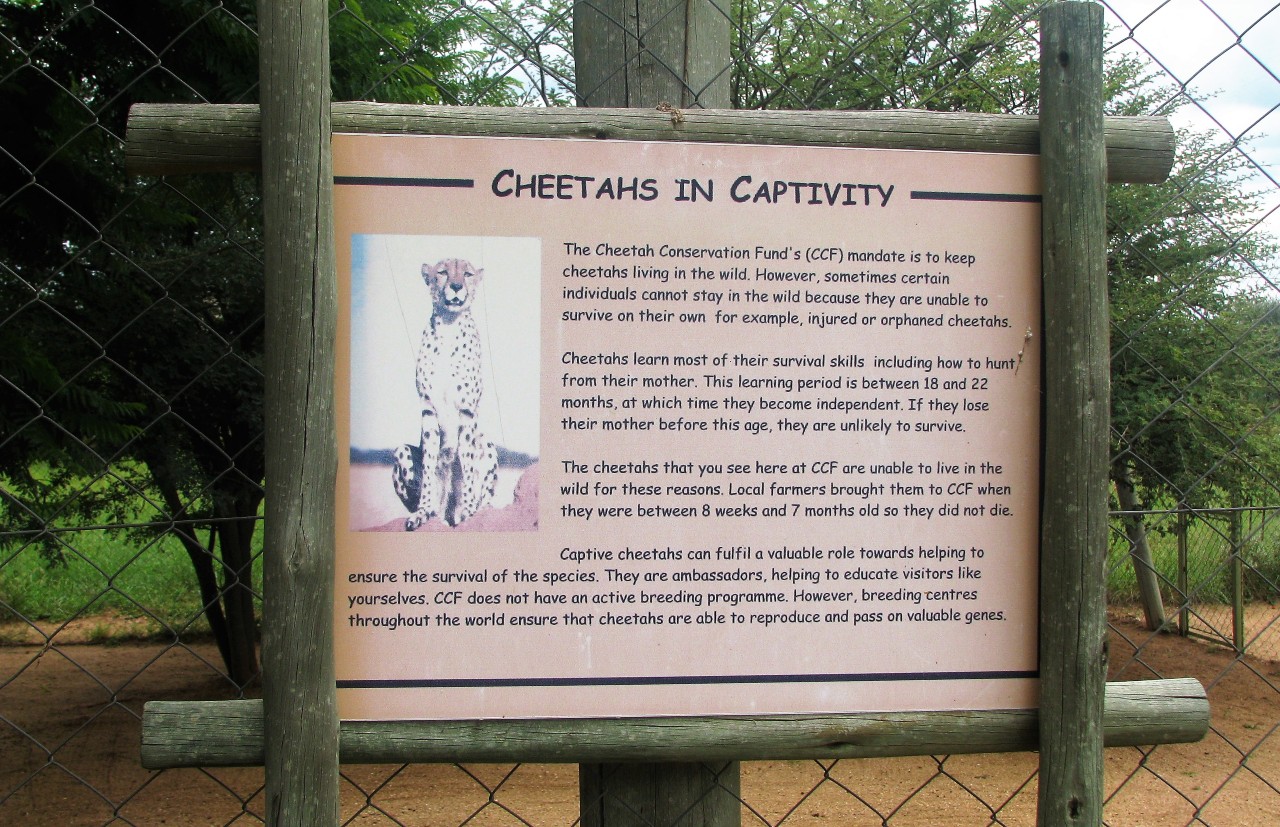

The quest to see this wildlife up close is on every traveller’s wish list – and thanks to conservation efforts and an amazing network of National Parks, reserves, and conservancies this seldom goes unrewarded. Much of Namibia’s story revolves around this wildlife and the communities that derive their income from it. We started our Namibian adventure with a visit to the Cheetah Conservation Fund Namibia (CCF) which is home to cheetah that are unable to be returned to the wild. Whilst I prefer to see wildlife in its natural habitat, it was the educational aspect that really impressed me here. With 90% of Namibian cheetahs living on livestock farms, CCF works actively with local farming communities to reduce this conflict through education and their successful Anatolian Shepherd dog project.

These special dogs, raised and bred here, are given free to Namibian farmers to help protect livestock from cheetah attacks, barking loudly whenever they see a cheetah or predator, scaring the big cats away. With most farmers reporting a 100% reduction in livestock kills by cheetahs and other predators there is no longer the need for them to kill cheetahs to protect their livestock and their livelihood.

The distances in Namibia are vast but there are enough distractions and ever-changing scenery to keep the road trip interesting. We came across Matlheo Kemko selling giant mushrooms on the roadside – these emerge around the termite mounds in the rainy season and are quite a delicacy.

Just beyond Tsumeb the terrain began to change once again and we began to encounter the Makalani Palms, standing tall above the surrounding bush. A great place to break the journey on-route to Etosha is at the Treesleeper Camp, a beautiful eco-friendly camp site nearby the village of Tsintsabis. It is a community based sustainable tourism project with a strong focus on the culture of the San people.

The name ‘Treesleeper’, a translation of their name Hai//om, is the name given to the Etosha San people for their practice of climbing up and sleeping in trees to keep out of the way of lions, cheetahs, and other predators. A guided bush walk is an ideal way to learn about the traditional way of life of the San people and the relationship they have with nature. Our guide entertained us with tales of bravery, hunting methods, medicinal cures from plants and of course demonstrated how to make fire by rubbing sticks – even with slightly damp wood, he still managed to get a spark!

Treesleepers Camp is committed to using solar energy wherever possible and all warm water at the camp site is provided by solar geysers, every camp site has two solar lights and the electricity at the cultural centre is provided by a solar panel.

The Etosha National Park was claimed as Namibia’s first conservation area in 1907 and has become one of Africa’s best game reserves. Its terrain contrasts from the vast, shallow pan of silvery sand in the east to sparse shrubs, grassy plains, and hilly Mopane woodlands elsewhere, totalling 22,000 sq. km. We experienced Etosha in the wet season, probably not the best time of year for the phenomenal wildlife sightings that the Park is renowned for, but incredibly rewarding all the same. The dry season’s sandy pan had been transformed into an inland sea, in some places its shallow waters stretching as far as the eye could see.

The dry plains were now covered with a wide variety of flowering plants and more grass species than I ever knew existed. The wet season offers spectacular birding and more than enough wildlife to make the low season worthy of a visit. The lack of crowds being a distinct advantage.

Visitors to Etosha have a choice of six Namibian Wildlife Resorts rest camps – we had the privilege of staying at the low impact, environmentally friendly establishment Onkoshi Camp that nestles on the rim of the Pan on a secluded peninsula.

Having only 15 units (30 beds), Onkoshi Camp offers a truly personal and exclusive experience. The location is entirely out of view from the accessible tourist routes and after arrival in Namutoni, we were transported by game viewing vehicle to the Camp.

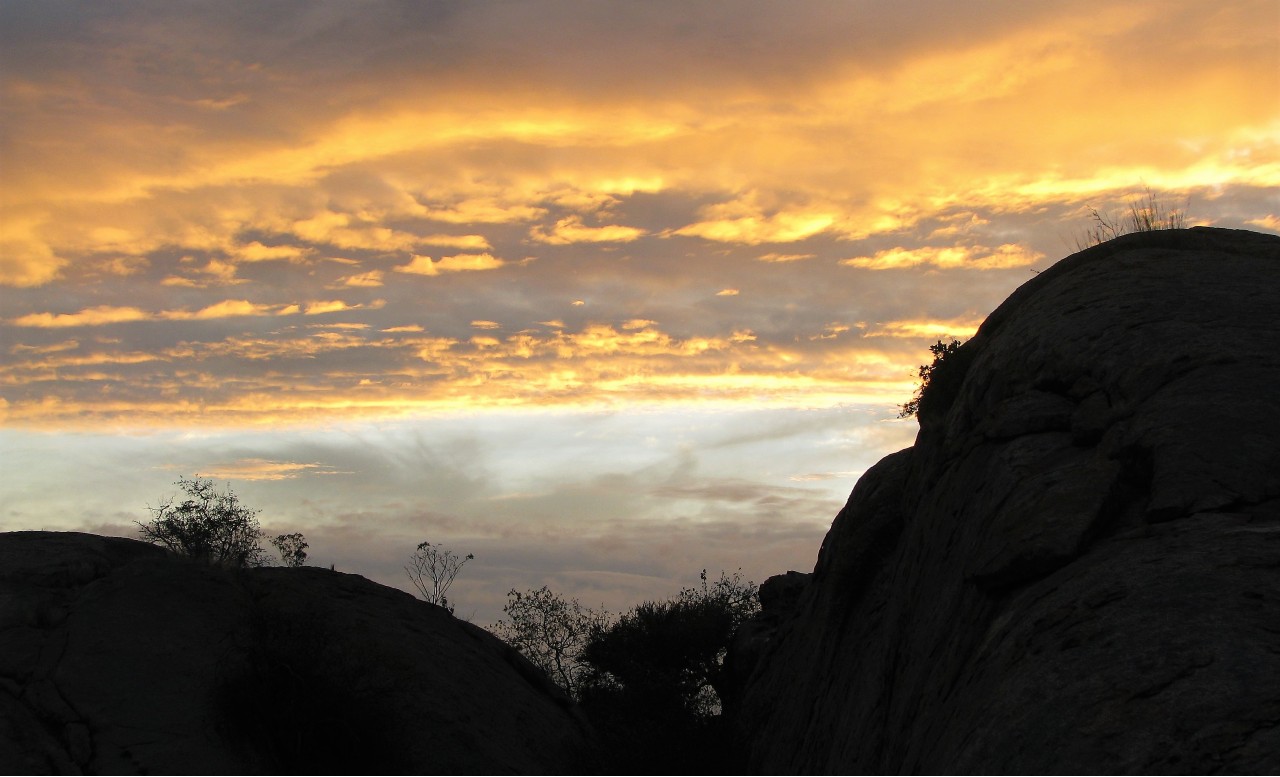

Each room is built on an elevated wooden deck, with thatched roof, canvas walls and large, wooden-framed retractable door allowing spectacular panoramic views across the Pan – the sunset was dramatic, and the sunrise equally memorable. But it was the sense of isolation and space, the clear night skies and the vastness – and not to mention the luxury, that made this such a highlight.

Etosha Village is an alternative to staying at one of the camps within the National Park and is situated just two km from the Andersson / Okaukuejo gate. The lodge is built in a traditional African village style with natural and traditional building materials and offers fully air-conditioned units on wooden decks with an en-suite bathroom. Other facilities include a unique bar (bar stools and lighting are made from re-purposed car parts), three swimming pools (re-purposed paint tins being the seating of choice) plus a shop and a restaurant serving magnificent buffet meals.

Etosha Village has implemented strict water saving measures, recycling water, using solar water heaters, supporting indigenous vegetation and using invasive trees for the building of wooden decks, etc. The recycled water enables them to have an organic vegetable and herb garden which is maintained by some of their staff members who then supply the lodge daily with fresh herbs and vegetables.

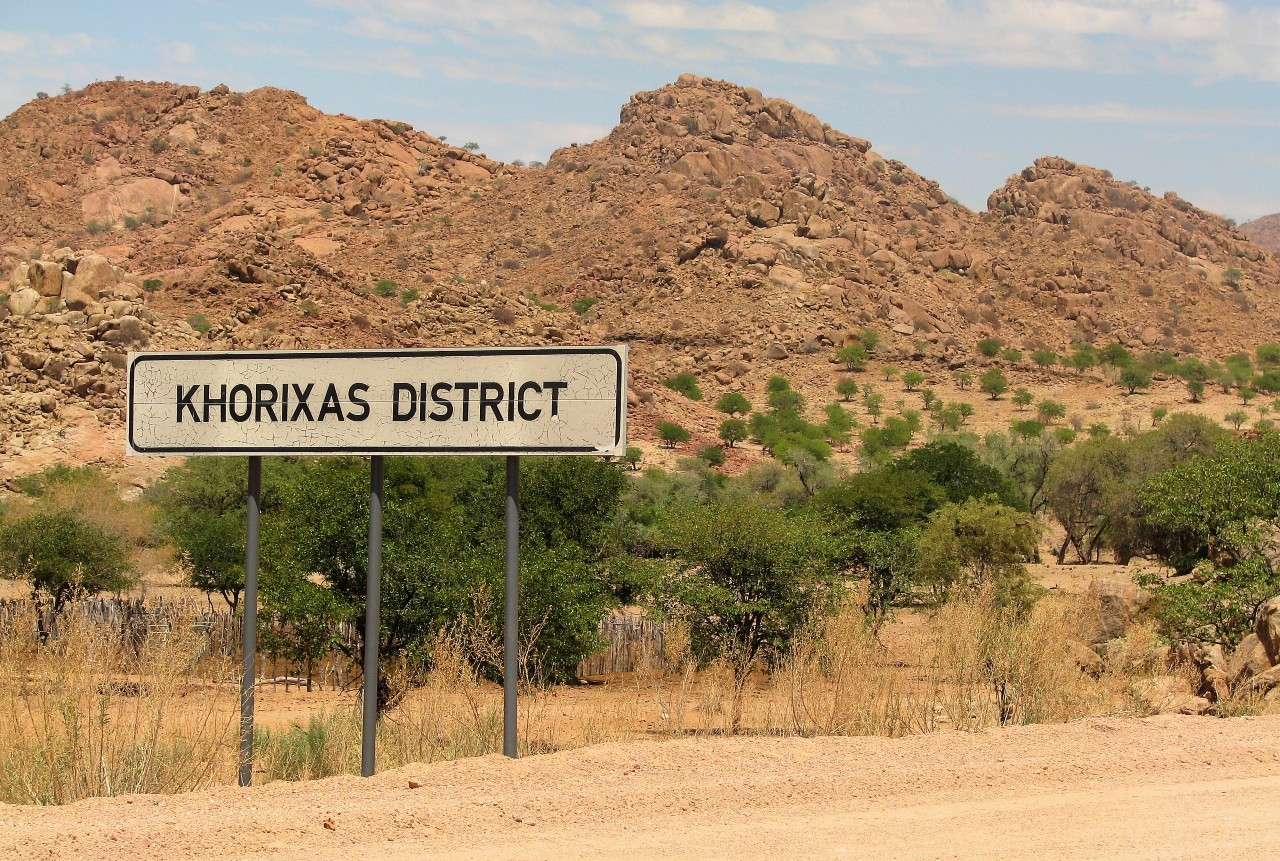

As we travelled west the vegetation grew more and more sparse and the lack of rainfall more obvious. This was the Namibia I had imagined, not the lush green vegetation of the eastern region. The Khorixas District is known for its desert elephants – so named for their adaptation to the area – and the elaborately dressed Herero women, their headdresses said to represent cattle horns.

The closest we came to the desert elephant was a warning sign on the road, but we were fortunate enough to be able to purchase some beautiful, crafted fabric products from a roadside stall operated by some enterprising Herero women and had the pleasure of watching Enethe Muheva dexterously manoeuvre the tiny pieces of fabric required to create a little Herero doll on her old Singer sewing machine.

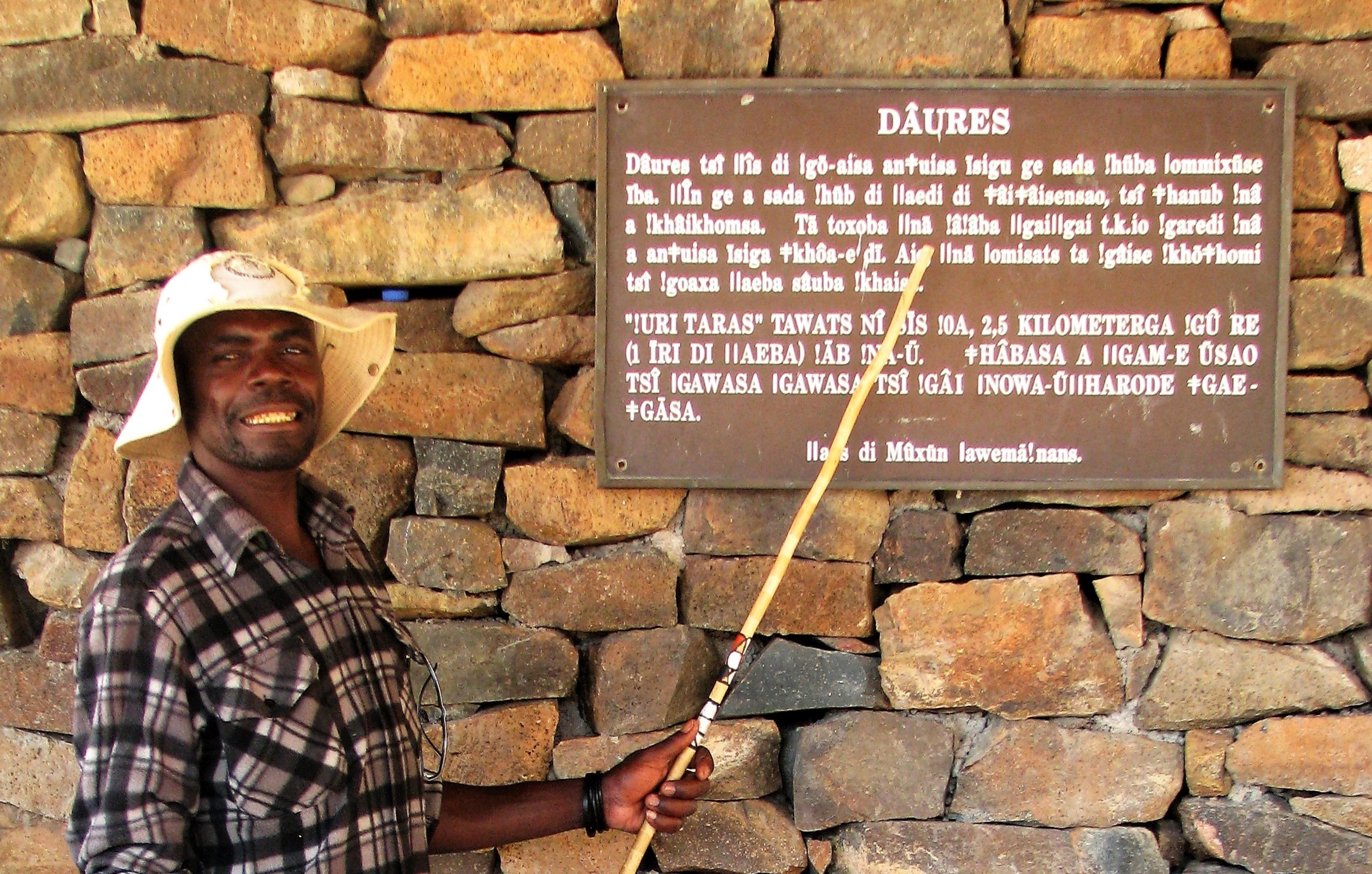

We were heading towards Namibia’s highest mountain, the Brandberg Mountain, its summit reaching 2573 meters above sea level. It is located in the north-western region of Damaraland in the Namib Desert, and because of its significance and rich biodiversity has been declared a national monument in Namibia.

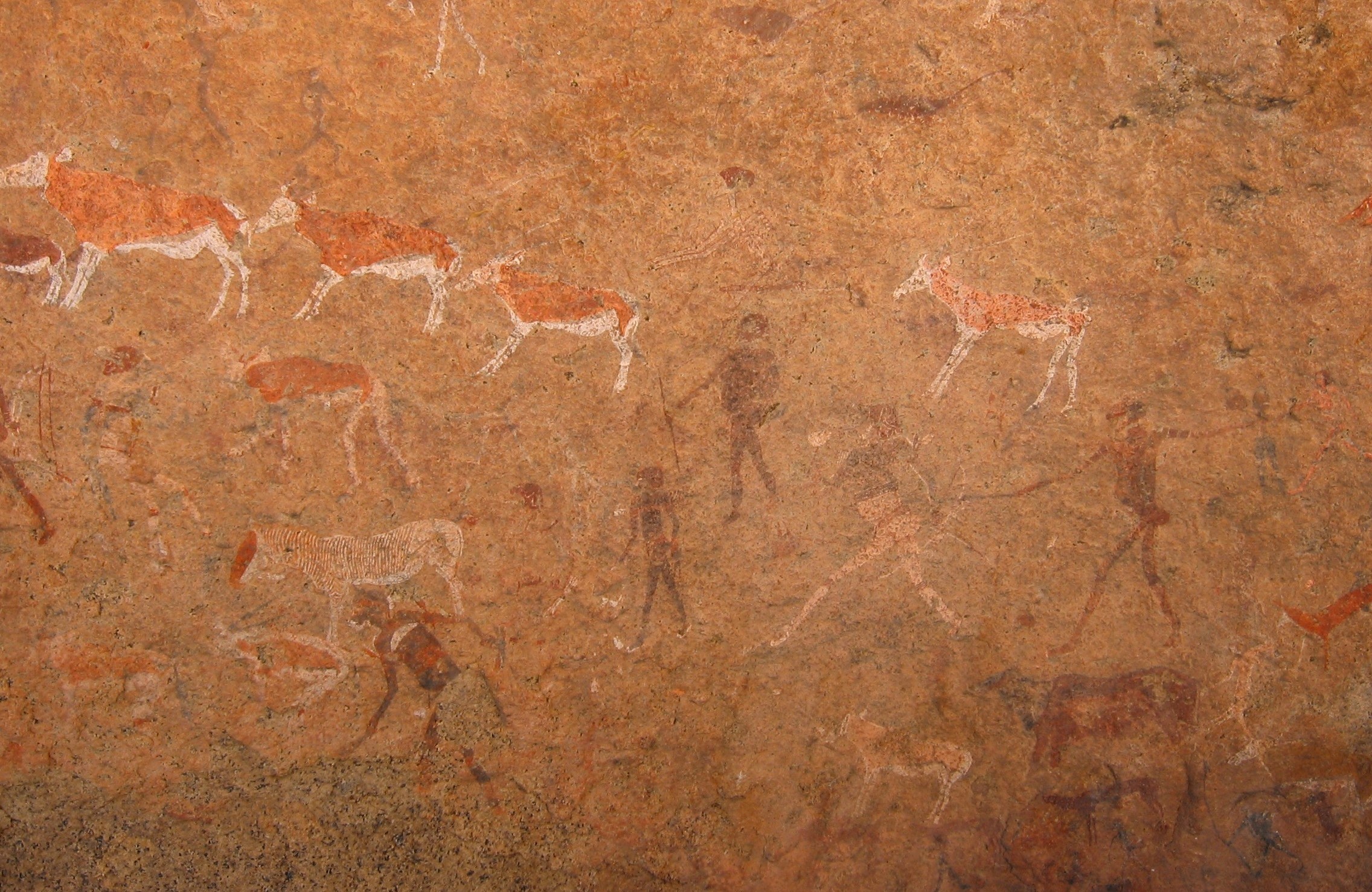

The name Brandberg is Afrikaans and German for ‘Burning Mountain’ – its name resembling the blazing glow which can sometimes be seen at dawn or sunset – personally, it was the piles of ‘burnt charcoal’ on the hillsides that named it for me. We weren’t here to study the intriguing geological features however, but one of the ancient rock art paintings hidden on the slopes of the mountain.

After a serious safety briefing (summer temperatures can be in excess of 40 degrees) and accompanied by our qualified professional local guide we set out to find The White Lady (who is in fact a male). This 2000-year-old San painting was first discovered by Dr Reinhard Maack in January 1918 while conducting surveys on Brandberg. Following a challenging 40-minute walk, traipsing over rocky terrain along the ancient mountain watercourse in the dry Tsisab Ravine, we found ‘her’, tucked away on a rock face under a small overhang.

While walking through the virtually untouched and preserved ecosystem we were hoping for a glimpse of the elusive desert elephant, which to our disappointment remained so, but we did get to see the dainty Damara dik-dik, some interesting birds as well as a rock agama lizard hiding amongst the rocky outcrops.

As we drove south the promise of long-awaited rains was in the air and our arrival at the Erongo Mountain Nature Conservancy was preceded by a wonderfully welcome downpour.

The lodge we stayed Erongo Wilderness Lodge, now under new ownership as The Erongo Wild, is nestled amid granite formations, its luxury tented chalets set amidst large boulders each with spectacular views and utmost privacy – except for an inquisitive dassie that took delight in peeking into my ‘outdoor’ bathroom. Flanked by the Namib Desert to the west and mixed-woodland savannah to the east, the mountains form a rare mix of ecosystems that give rise to remarkable biodiversity, including a vast array of plant, reptile, mammal, and bird species that are endemic to Namibia.

The Erongo Mountain Nature Conservancy joins private landowners in a collective effort to conserve and protect this natural treasure of over 200 000ha in extent. This includes the preservation of the rich cultural heritage in the form of rock paintings and engravings that are found throughout the area.

Walking is the best way to experience the beauty of the Erongo Mountains and local guide Johnny shared his knowledge of the local fauna, flora, and folklore as we walked over granite domes and through rich valleys. Birding is a popular drawcard to the area, with the immediate vicinity of the lodge being home to over 50 different species, including Namibian endemics the Hartlaub’s francolin and rosy-faced lovebird and many more. In addition to this the nests of two breeding pairs of Verreaux’s eagles can be seen on cliff faces, with sightings of this magnificent bird occurring nearly every day.

All too soon we were headed back to Windhoek to catch our flight back to South Africa, sad to leave but encouraged by the knowledge that tourism dollars spent here will have a real, sustainable impact on environmental and wildlife conservation as well as the communities that rely on them.

Words & pics Tessa Buhrmann